# How Channel Capacity and Liquidity affect Payment Routing

# Lightning Network explained

The Lightning Network is a second layer scaling solution for Bitcoin and similar cryptocurrencies. It promises faster transactions and lower fees, enabled by a network of bidirectional payment channels. This post shows how channel capacity and liquidity affect payment routing in the Lightning Network.

In the article about the lifecycle of a payment channel we learned how basic transactions work. Beyond that, the Lightning Network – being a network of payment channels – enables transactions across channels as well. Payments can be routed across multiple hops until they reach the payee. However, the channel capacity and liquidity along the route play an important and constraining role in pathfinding.

# Definitions

Capacity is defined as the total amount of funds in a payment channel. Once a channel is created the capacity is fixed as the funds get settled by the funding transaction.

The term balance describes the distribution of funds between the channel peers. Terminology-wise the balance affects liquidity, as we need to distinguish between inbound and outbound liquidity.

From a user’s perspective, inbound liquidity are the funds on the remote side of the channel; the amount that the user would be able to receive.

For example merchants would primarily need inbound liquidity in order to receive payments.

As the exact opposite outbound liquidity are the funds on the own side of the channel; the amount that the user would be able to send.

Normal users/customers mostly need outbound liquidity to make payments and purchase goods.

Routing describes the process of finding a payment path for peers that have no direct channel connection. Pathfinding is constrained by the capacity and liquidity along the route. As a general rule of thumb you can say, that the longer the path, the more limiting these factors will be.

Sidenote: Hash Time-Locked Contracts (short: HTLC) are used to secure the funds while they are moving along the route. They ensure that the money does not get stolen on its way to the payee. The nodes along the route can charge fees as a commission for their service. These fees are also included in the HTLC each peer passes on. Both, the HTLC and fees are topics in their own rights and might be discussed in a future article.

# Routing constraints

With these definitions out of the way, here is an analogy that might help to understand the movement of funds:

Imagine the funds in a payment channel as beads on a string.

Or for the elderly among us: as beads in an abacus. 🧮

They can travel from one side to the other, but won’t leave the string, even when they are routed.

The number of beads (capacity) is fixed and the side they are on (balance) symbolizes either in- or outbound liquidity.

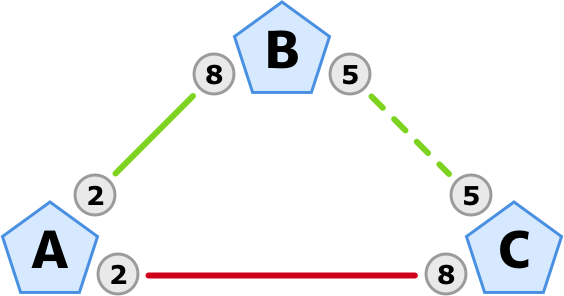

Enough of the dry theory, let’s have a look at a practical example: The following diagram shows a case, where Alice wants to pay Charlie the amount of 4 mBTC (the unit for the examples is arbitrary). The balance of her own channel with Charlie does not suffice: She only has an outbound liquidity of 2 (red line). But her channel with Bob has an outbound liquidity of 6, so the payment can embark on that route (dashed green line).

So Alice creates a commitment transaction with an HTLC, which grants Charlie the amount of 4. She sends it to Bob, so that he can pass it along.

At this point, the payment could still fail: Namely in the case that Bob’s outbound capacity to Charlie would not suffice (dashed gray line). What trips up most people in their understanding: Bob cannot and take the 4 he received from Alice, move them over to his channel with Charlie and pass them on. The funds can not directly „change the channel“: As eachs channel capacity is fixed, the routing only works if Bob’s outbound capacity in his channel with Charlie is at least 4 …

# Balance changes

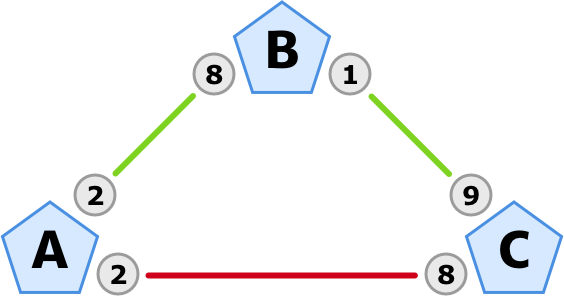

Luckily for Alice this is the case: Bob has an outbound capacity of 5 in his channel with Charlie. The payment gets routed as we can see in the following sequence of diagrams.

This is what the balances look like after the routing operation has succeeded:

Sidenote: Because of the HTLCs, routing operations are atomic. This means that either the entire operation succeeds or nothing happens. But for the sake of a more comprehensible explanation the diagrams show a gradual way of the funds travelling.

As we can see, routing the payment from Alice to Charlie through Bob changed the balances of all channels along the way:

- A-B moved from 6-4 to 2-8

- B-C moved from 5-5 to 1-9

This is especially of importance for another type of stakeholders in the system: Routing node operators have to constantly rebalance their channels to provide the right kind of liquidity for the respective flow of funds.

To briefly summarize these points, one could say that …

- Merchants need inbound liquidity.

- Customers need outbound liquidity.

- Routing nodes have to adjust their channel balances based on the flow of funds.

These points are a big topic regarding the adoption currently: As channel capacity and liquidity are the constraining factors, there are already services catering to the needs of merchants: The Lighting channel-opening service Thor by Bitrefill was the first to my knowledge, quickly being followed by Lightning Labs’ Loop.

# Future development

But not just merchants are dependent on inbound liquidity. As we have seen, customers will encounter limitations based on the length of their payment route.

To accommodate for that, solutions like Multi-Path Payments (short: MPP) are already being worked on: Instead of traveling along a single route, the funds can be split up and take several different routes. This way larger payments will be enabled as the capacity and balance of multiple channels can be factored in. For example: With MPP, Alice’s payment to Charlie could be split up to 2 mBTC going through Bob and the other 2 mBTC using another node D as a hop.

This is just one of many exciting features that are currently finding their way into the Lightning Network specification. Stay tuned for more on that 😀